TMS Improves Memory via Brain Surface Networks

Nancy A. Melville | August 28, 2014

Copyright © 2014 by WebMD LLC. All rights reserved.

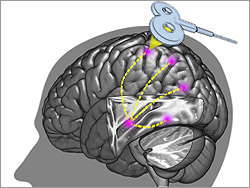

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) improves memory by activating a network of surface brain regions that interact with the much deeper center of memory, the hippocampus, a new study suggests.

While rTMS is used in psychiatry and has approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of depression, the findings have potentially important neurologic implications — suggesting a means of manipulating the all-important but deeply located hippocampal structure without surgery.

“No one has targeted this network of regions associated with memory before with rTMS,” senior author Joel Voss, PhD, told Medscape Medical News.

“Most thinking in rTMS research has been that you are only going to have an effect on the very superficial parts of the brain that you can actually directly stimulate, because the electrical current doesn’t go very deep,” said Dr. Voss, an assistant professor of medical social sciences at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, Illinois.

“But we said ‘let’s see if stimulating those areas closer to the surface of the brain that are known to be disrupted in memory disorders can have an effect in changing the broader hippocampal network,’ and we found that to be the case.”

The findings are published in the August 29 issue of the journal Science.

Healthy Adults

The study involved 16 healthy adults, aged 21 to 40 years, who were treated with rTMS for 20 minutes per day over the course of 5 days.

Before the treatment, the patients were evaluated in a resting state with functional MRI (fMRI) to identify the location of the lateral parietal cortex component of the cortical-hippocampal network, which is the hypothesized memory-connection region, and the rTMS signal was targeted accordingly.

Compared with sham control conditions involving subthreshold intensity for neural stimulation, post-treatment fMRI assessments, made 24 hours following the stimulation, showed significantly greater improvements in connectivity over baseline in 4 regions known to have hippocampal connectivity: the precuneus/retrosplenial cortex, the fusiform/parahippocampal cortex, the superior parietal cortex, and the left lateral parietal cortex.

Likewise, when given face-cue and word-recall tests in associative memory, the participants showed corresponding improvements 24 hours after treatment over baseline that were significantly greater compared with sham conditions (P = .008). Participants showing larger stimulation-induced connectivity changes on fMRI showed greater memory improvements.

The authors noted that “fMRI connectivity changes were remarkably specific for hippocampal targets, were significantly correlated with associative memory improvements, and did not occur when a motor-cortex region distinct from cortical-hippocampal networks was stimulated in the control experiment, providing strong evidence against (various) possible nonspecific influences.”

While the intensity of the current in rTMS, 3 Teslas, is quite strong — approximately 100,000 times the magnetic field of the earth, according to Dr. Voss — it rapidly drops off after leaving the coil and therefore only penetrates the brain less than a centimeter. Side effects are said to be minimal and rare, and the authors reported none in the current study.

“In terms of long-term effects, we don’t know for sure, but just looking at the magnitude of the effect on the brain it’s very unlikely there is any lasting effect after a few days,” Dr. Voss said.

The study’s findings of improvement for up to 24 hours after treatment is especially notable and encouraging in terms of possible therapeutic applications for people with memory impairment, he added.

“An exciting thing about this is that now that we know that we can actually modulate this memory network, we can look into various disorders, such as stroke, mild cognitive impairment, traumatic brain injury, or even schizophrenia and see the extent to which this may be able to improve symptoms and hopefully have an effect on people’s memories,” Dr. Voss said.

Important Insights

Neurologist Daniel C. Potts, MD, a member of the American Academy of Neurology and associate clinical professor at the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, said he agreed that the study offers important insights on the role of rTMS in memory.

“I think the results of the study, though conducted in a small number of subjects and in need of confirmation in larger trials, is exciting and promising,” he told Medscape Medical News.

He noted previous research demonstrating rTMS to have improvement in human motor systems, learning and working memory, including a recent study, reported by Medscape Medical News, from Toronto, Ontario, Canada, in patients with schizophrenia, but the new study appears to be the first of its kind.

“For me, the clinical significance is primarily that rTMS appears to be strengthening functional connectivity and performance in targeted neuronal memory circuits, including eliciting changes in neuroplasticity which may be more sustained,” he said.

“This obviously would give rTMS promise in enhancing memory performance in persons with cognitive disorders, potentially even those with dementia and/or Alzheimer’s disease, though I think it is too early to step out and make that broad assertion.”

The use of this technology in Alzheimer’s would be a significantly new approach to the disease, he added.

“Because the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s adversely affects hippocampal structure and function, the greatest clinical importance would have to be based on the assertion that residual hippocampal tissue could presumably be recruited into circuits involved in elements of memory, thereby preserving or improving function, and the authors raise this point,” he concluded. “One would certainly hope this would be the case, but this remains to be proven.”

The research was supported by awards from the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The authors and Dr. Potts have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.